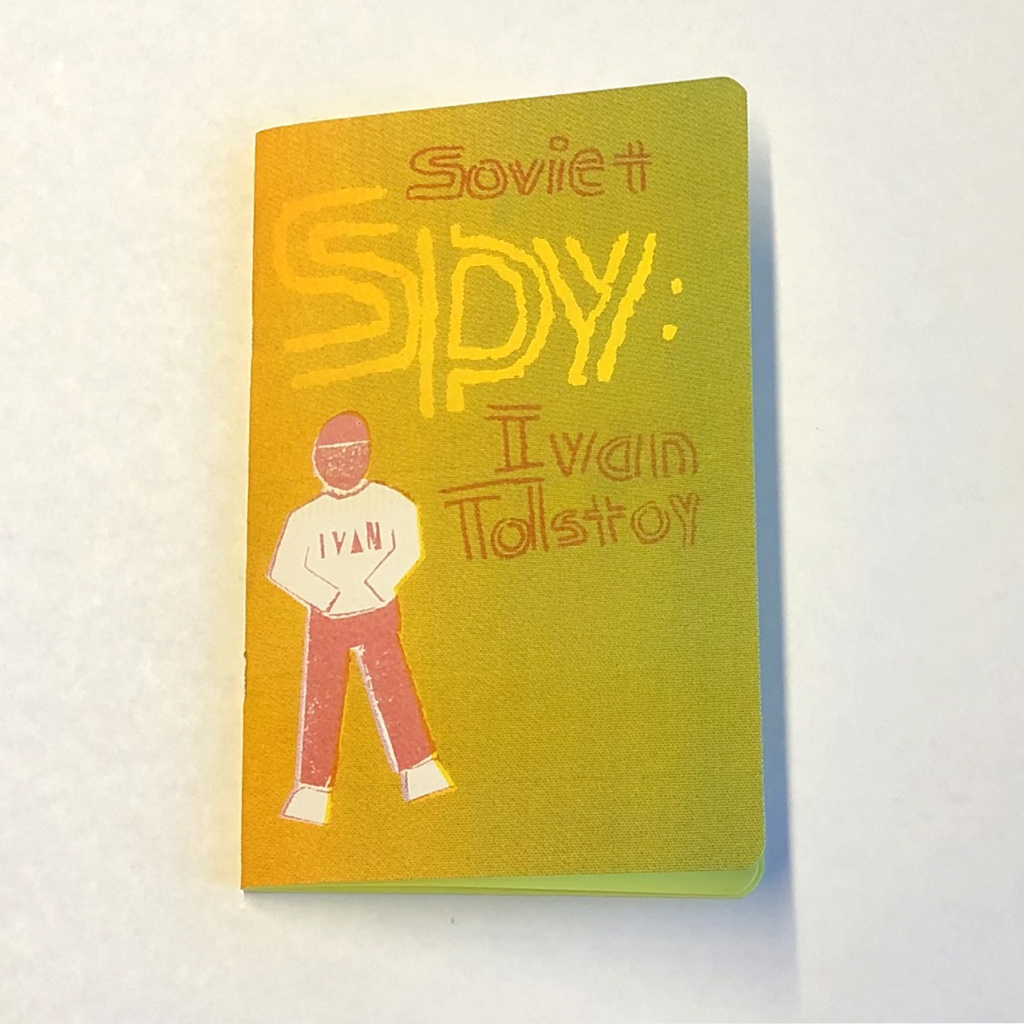

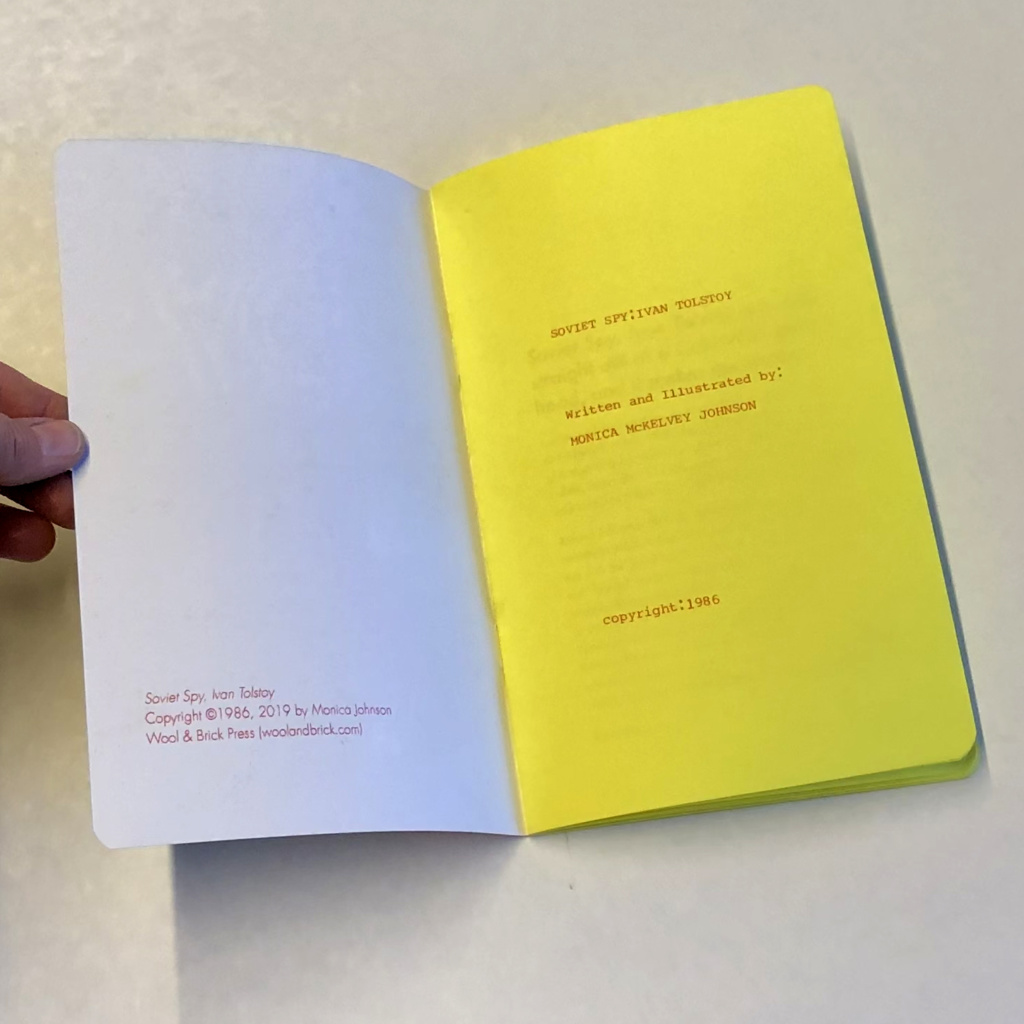

Soviet Spy, Ivan Tolstoy

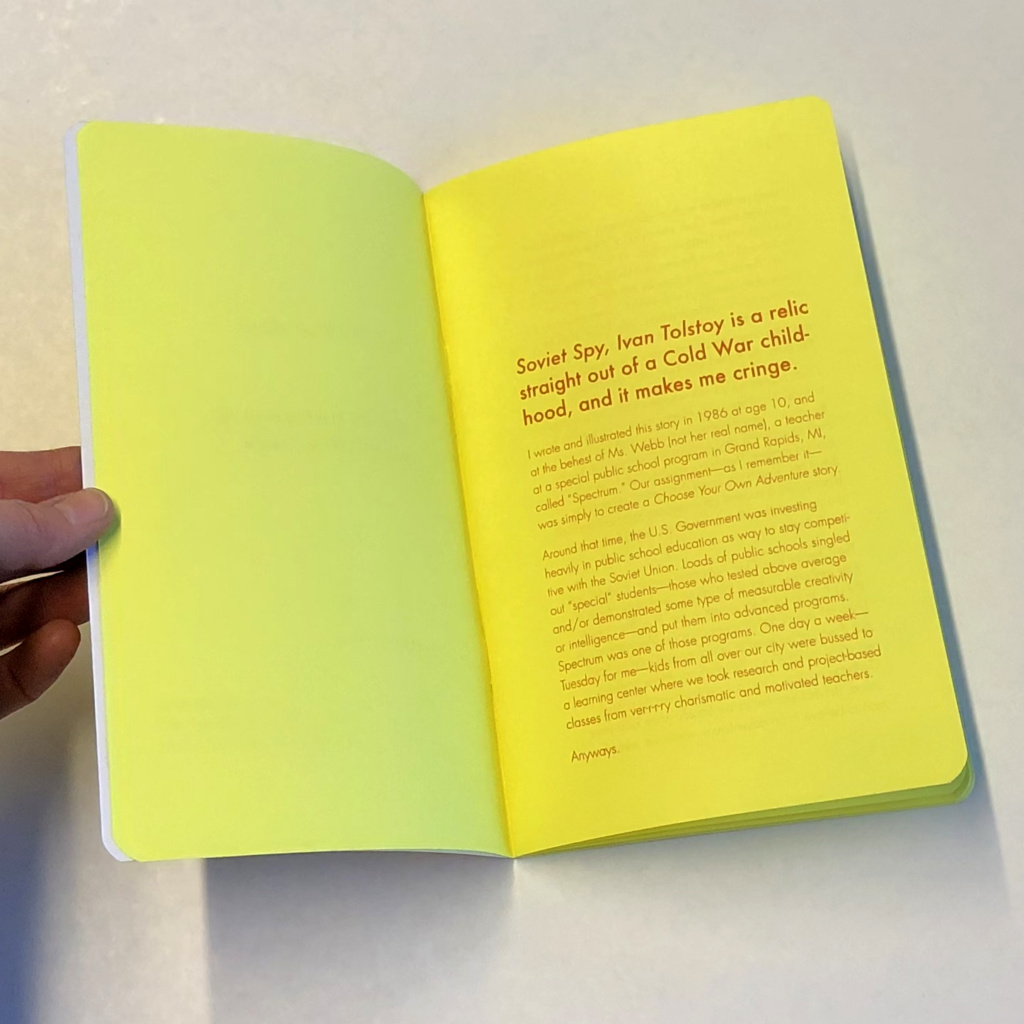

Soviet Spy, Ivan Tolstoy (1986, 2019) is a relic straight out of a Cold War childhood, and though it is a cringy read to be sure, it is also clear evidence of U.S. Imperialism within 1980s public school education.

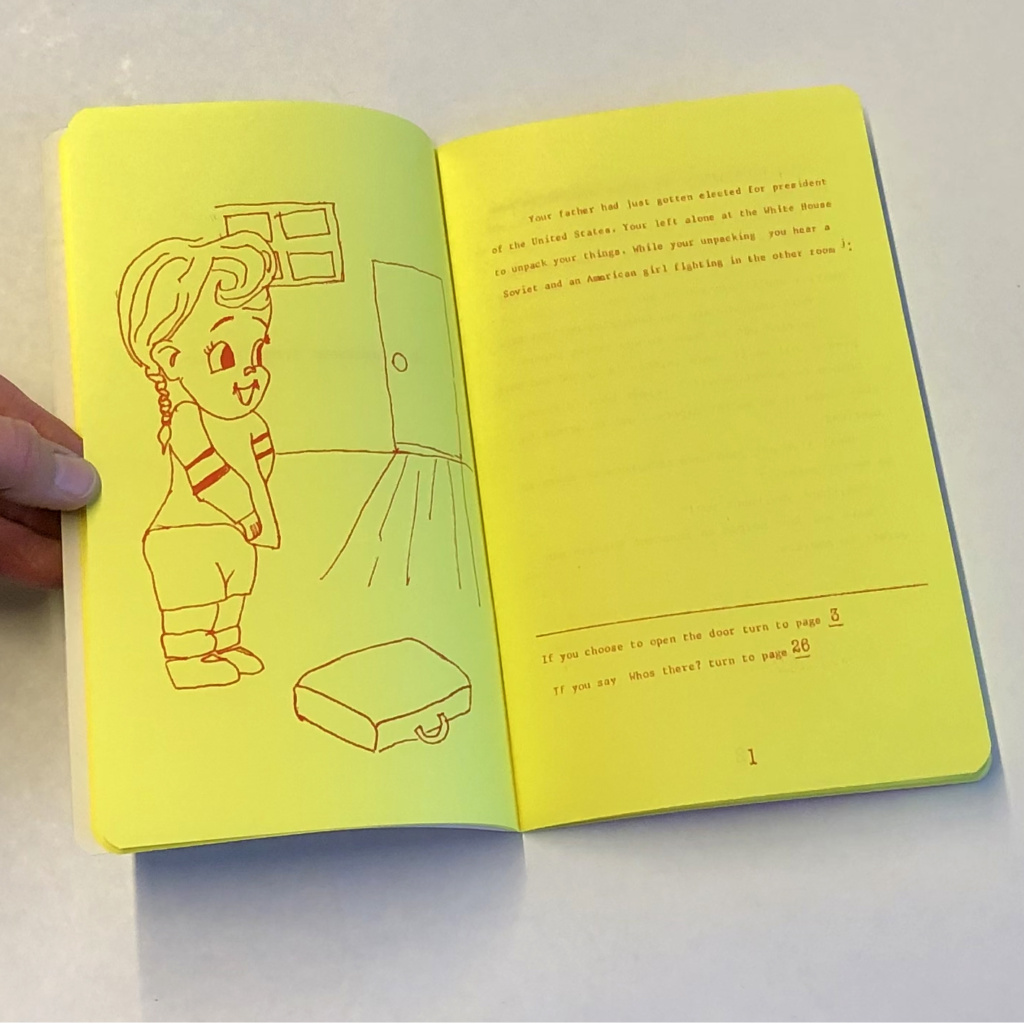

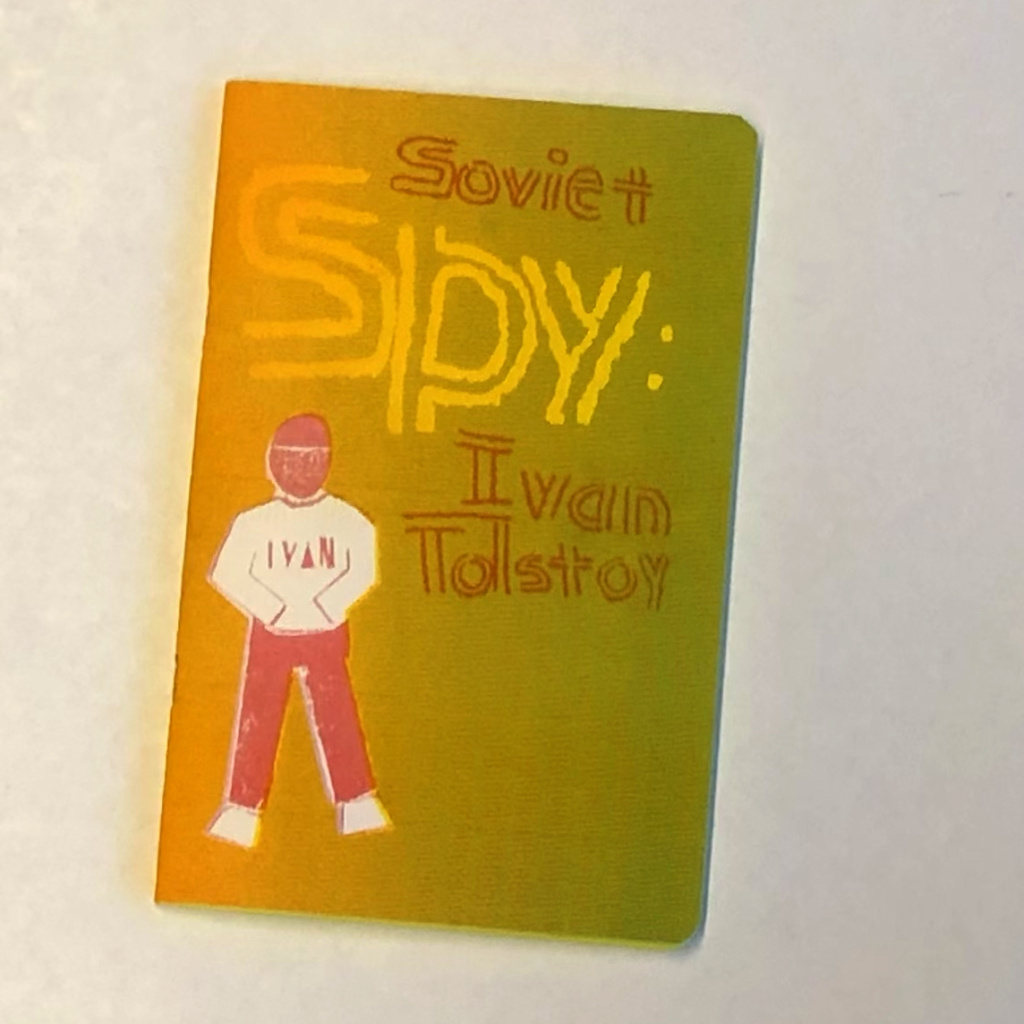

Johnson wrote and illustrated this story in 1986 at age 10, and at the behest of her teacher public school teacher, Ms. Webb, (not her real name). The assignment was simply to create a Choose Your Own Adventure story, but Johnson goes on to situate Soviet Spy to embody a lot of what was wrong with the blind optimism of the neoliberal 1980’s–that taught (mostly white) kids that all they had to do was believe in themselves, to choose their own adventures and the world was there for the taking. And speaking of, Johnson was allowed to appropriate the name “Tolstoy”, the name of a legendary and accomplished writer, and distort it into a dufus-villain whose character extended the xenophobia du jour. She was allowed to copy a cartoon character that was not her own and insert it into the story as her own.

oviet Spy, Ivan Tolstoy is a relic straight out of a Cold War childhood, and though it is a cringy read to be sure, it is also . Johnson wrote and illustrated this story in 1986 at age 10, and at the behest of her teacher public school teacher, Ms. Webb, (not her real name). The assignment was simply to create a Choose Your Own Adventure story, but Johnson goes on to situate Soviet Spy to embody a lot of what was wrong with the blind optimism of the neoliberal 1980’s–that taught (mostly white) kids that all they had to do was believe in themselves, to choose their own adventures and the world was there for the taking. And speaking of, Johnson was aloud to take the name “Tolstoy”, the name of a legendary and accomplished writer, and distort it into a dufus-villain whose character extended the xenophobia du jour. She was allowed to copy a cartoon character that was not her own and insert it into the story as her own.

Around that time, the U.S. Government was investing heavily in public school education as way to stay competitive with the Soviet Union. Loads of public schools singled out “special” students—those who tested above average and/or demonstrated some type of measurable creativity or intelligence—and put them into advanced programs.

I don’t remember much about creating Soviet Spy, but as I read it now I can identify a lot of the American culture and ethics I was raised on. At the time I wanted to be Samantha from the sitcom, Who’s the Boss, which is why the protagonist goes by that name. I notice traces of my obsession with WWF Wrestlemania in the narrative when I nickname Ivan, “Mr. T,” or when he puts Samantha in a “Full Nelson.” And I totally plagiarized the character design from some popular cartoon that goes uncredited and that I can’t remember.

I didn’t consciously know who Leo Tolstoy was enough to know I had obviously mis-appropriated his name for the villain’s, and therefore stereotyped all Russians-—even epically talented authors of yore—as evil, buck-toothed morons. That bums me out a lot. How was it that Ms. Webb accepted that kind of xenophobic bigotry from a student? I’m even more surprised because she was a queer, disabled teacher. Is that fair of me? No. But still.

The Choose Your Own Adventure format of Soviet Spy itself embodies a lot of the idiotic, neoliberal ideals of the U.S. public school system in the ‘80s, from which I/we still feel negative reverberations. We were taught that if we just believed in ourselves and worked hard, we could do anything. Be anything. Have anything. Garbage advice, if you ask me because it’s patently untrue. But that was life as we (mostly white kids) were lead to believe it: an adventure in which we were the “choice directors.” As a result of this misleading encouragement—coupled with the reality of its untruth—we now have a nation of (mostly white) narcissists with underdog complexes. That’s easy psychology to navigate. :-/

So when I rediscovered Soviet Spy, Ivan Tolstoy in my dad’s basement a few years ago I probably should have enjoyed the nostalgia for what it was worth, burned it, and pretended it never happened. But I couldn’t resist the opportunity to critique it. Critiquing my past, rather than blindly celebrating it’s anecdotes, offers me another way to revise, re-edit, and reconstruct myself as an adult . . . who does not want to be another narcissistic underdog. Fuck nostalgia anyways.

So, here is this artifact of a my bigoted, imperialist, Cold War era, American public school education. May it not be replicated.

Risograph printed illustrated zine

Saddle bound, 36 pages, 8.5″ x 5.5″